#1903 Letters & Diary entries

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Letter excerpt from Princess Marie of Romania to

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna

Castel Peles, 22 August 1903

Dear Mama,

(...)

The other children are intensely excited and delighted, it's killing to hear their conversations about the new little brother (Nicolae). Carol feels as if he had triumphed them all because it is a boy whilst my daughter encouraged by Cousin Ella, come & try to persuade me to let its hair grow that it should become a girl; whilst Mignon is simply enchanted with it at it is.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

image: princess Elisabeth of Hesse sitting between her Romanian aunt and cousins: Princess Marie, Princess Elisabeta and newborn Mignon in 1900

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

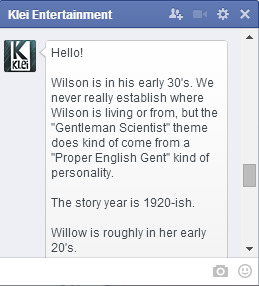

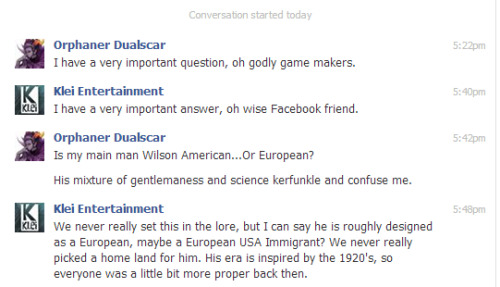

Approximately when some of the DST characters were born

(Reminder this is all speculation!! And since we don’t have an age range for some of the characters, I will have to guesstimate*)

*guess-estimate

(OKAY SO… This has been in my drafts for a year-ish.. I planned to do more characters but lost my motivation, and now I am finally posting it)

Wilson: Born sometime around 1887-1891 on April 23. Probably born in Europe and possibly immigrated to America some time before he was taken.

He has been stated to be in his early 30’s in a Klei facebook message/post (I dont really know how to describe it) on June 17, 2014

Wilson was also canonically taken into the constant in the year 1921. This is stated in a rough timeline made by Klei developer Kevin Forbes on September 25, 2014. He is in his early 30’s (30-34) and taken in 1921, 1921 minus 34 is 1887 and 1921 minus 30 is 1891 so he was born around those years. It isn’t really set in stone if he is European or not, but it is sorta hinted to. On January 7, 2014 in a Facebook conversation it is stated that he is “roughly designed as a European, maybe a European USA Immigrant”

Willow: Possibly born around 1887-1891 on May 7. She was orphaned at a young age and then sent to an orphanage, then she burnt it down.

This was a lot harder to figure out, and with new lore always coming this birth year speculation may be proven wrong. As seen above in the first image Willow is in her early 20’s. (Also, Willow was first said to be in her Late teens, and then later said to be in Early 20’s. Personally I take the early 20’s to be more canon as it was said at a more recent time than the first age.) There is no set in stone time for when she was taken. With the knowledge of the date Wickerbottom was taken (March 29, 1911, said in the timeline I linked above ^^) we can assume she was taken sometime between 1911-1921 (1921 is when Maxwell takes in Wilson, presumably his last victim) She was probably taken not to long after Wickerbottom was taken because Willow in the constant looks the same as Willow in Wickerbottoms animation. 1911 minus 20 is 1891 and 1911 minus 24 is 1887.

Wendy: Born November 11, 1903.

I got this birth year from the timeline and it is also stated in Wendy's Dont Starve wiki page The reason the year chosen is 1903 is because “Wendy is stated to be between 8 and 10 years old. This range can be narrowed down by examining various dates from the William Carter puzzles and the image of her nightstand. Jack's letter in the third William Carter puzzle, which mentions the twins, must have been written no later than the August 1904 dates from the fourth puzzle. This means that Wendy and Abigail were born no later than August 1904. Additionally, Wendy's diary entry, which was likely written before she entered the Constant, has a date of April 16, 1914. Since Wendy's birthday is in November, her only possible date of birth is November 11, 1903.” This text is taken from the wiki linked above. ^^ If we take her diary entry and her birth year and do some math, we can figure out that Wendy is 10 years old and 5 months when she was taken into the constant.

#Don’t starve#dont starve#dst#wilson higgsbury#wilson percival higgsbury#dostarve speaks#dst lore#wendy carter#willow dst#dst wendy#klei entertainment#dont starve together#I talk about dst

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

✶ surprise me

send ✶ and I’ll write a headcanon about our muses

*cracks knuckles* okay here we go !

HARRY — whenever harry is feeling lonely (aka whenever stefan is off fixing d*mon's messes or out there doing hero hair hot guy shit) he finds himself looking up at the night sky and searching for the north star because it reminds him of his husband. stefan is his north star, shining brighter than any other star in the sky. while the moon is a reminder of his curse, the star is a reminder that he has a safe space and that no matter what happens, stefan will always find his way back to him.

VALERIE — in the 1903 prison world, valerie started journaling, but instead of starting each entry with 'dear diary,' she started them with 'dear stefan,' writing a different letter to him every day. sometimes she would tell him the truth about what happened, other times she would just tell him about her day, or about whatever was on her mind. it was therapeutic for her, and helped her work through her trauma. it was easy for her to write to him, knowing he would never read what she wrote. ( . . . BONUS FEELS : she would have named their child cassiopeia. )

#salvatoraes#HARRY BINGHAM — stefan salvatore.#VALERIE TULLE — stefan salvatore.#ANSWERED.#i'm not crying ur crying xo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...The letters, biographies, memoirs, and diaries that recorded Victorian women’s lives are essential sources for differentiating friendship, erotic obsession, and sexual partnership between women. The distinctions are subtle, for Victorians routinely used startlingly romantic language to describe how women felt about female friends and acquaintances. In her youth, Anne Thackeray (later Ritchie) recorded in an 1854 journal entry how she “fell in love with Miss Geraldine Mildmay” at one party and Lady Georgina Fullerton “won [her] heart” at another. In reminiscences written for her daughter in 1881, Augusta Becher (1830–1888) recalled a deep childhood love for a cousin a few years older than she was: “From my earliest recollections I adored her, following her and content to sit at her feet like a dog.”

At the other extreme of the life cycle, the seventy one-year-old Ann Gilbert (1782–1866), who cowrote the poem now known as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” appreciatively described “the latter years of . . . friendship” with her friend Mrs. Mackintosh as “the gathering of the last ripe figs, here and there, one on the topmost bough!” Gilbert used similar imagery in an 1861 poem she sent to another woman celebrating the endurance of a friendship begun in childhood: “As rose leaves in a china Jar / Breathe still of blooming seasons past, / E’en so, old women as they are / Still doth the young affection last.” Gilbert’s metaphors, drawn from the language of flowers and the repertoire of romantic poetry, asserted that friendship between women was as vital and fertile as the biological reproduction and female sexuality to which figures of fruitfulness commonly alluded.

Friendship was so pervasive in Victorian women’s life writing because middle-class Victorians treated friendship and family life as complementary. Close relationships between women that began when both were single often survived marriage and maternity. In the Memoir of Mary Lundie Duncan (1842) that Duncan’s mother wrote two years after her daughter’s early death at age twenty-five, the maternal biographer included many letters Duncan (1814–1840) wrote to friends, including one penned six weeks after the birth of her first child: “My beloved friend, do not think that I have been so long silent because all my love is centered in my new and most interesting charge. It is not so. My heart turns to you as it was ever wont to do, with deep and fond affection, and my love for my sweet babe makes me feel even more the value of your friendship.”

Men respected women’s friendships as a component of family life for wives and mothers. Charlotte Hanbury’s 1905 Life of her missionary sister Caroline Head included a letter that the Reverend Charles Fox wrote to Head in 1877, soon after the birth of her first child: “I want desperately to see you and that prodigy of a boy, and that perfection of a husband, and that well-tried and well-beloved sister-friend of yours, Emma Waithman.” Although Head and Waithman never combined households, their regular correspondence, extended visits, and frequent travels were sufficient for Fox to assign Waithman a socially legible status as an informal family member, a “sister-friend” listed immediately after Head’s son and husband.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf lamented that a woman born in the 1840s would not be able to report what she was “doing on the fifth of April 1868, or the second of November 1875,” for “[n]othing remains of it all. All has vanished. No biography or history has a word to say about it.” Yet as an avid reader of Victorian life writing, Woolf had every reason to be aware that in the very British Library where her speaker researches her lecture, hundreds of autobiographies, biographies, memoirs, diaries, and letters provided exhaustive records of what women did on almost every day of the nineteenth century.

One cannot fault Woolf excessively for having discounted Victorian women’s life writing, for even today few consult this corpus and no scholar of Victorian England has used it to explore the history of female friendship. Scholars of autobiography concentrate on a handful of works by exceptional women, and historians of gender and sexuality have drawn primarily on fiction, parliamentary reports, journalism, legal cases, and medical and scientific discourse, which emphasize disruption, disorder, scandal, infractions, and pathology. Life writing, by contrast, emphasized ordinariness and typicality, which is precisely what makes it a unique source for scholarship.

The term “life writing” refers to the heterogeneous array of published, privately printed, and unpublished diaries, correspondence, biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, reminiscences, and recollections that Victorians and their descendants had a prodigious appetite for reading and writing. Literary critics have noted the relative paucity of autobiographies by women that fulfill the aesthetic criteria of a coherent, self-conscious narrative focused on a strictly demarcated individual self. Women’s own words about their lives, however, are abundantly represented in the more capacious genre of life writing, defined as any text that narrates or documents a subject’s life.

The autobiographical requirement of a unified individual life story was irrelevant for Victorian life writing, a hybrid genre that freely combined multiple narrators and sources, and incorporated long extracts from a subject’s diaries, correspondence, and private papers alongside testimonials from friends and family members. A single text might blend the journal’s dailiness and immediacy and a letter’s short term retrospect with the long view of elderly writers reflecting on their lives, or the backward and forward glances of family members who had survived their subjects.

For example, Christabel Coleridge was the nominal author of Charlotte Mary Yonge: Her Life and Letters (1903), but the text begins by reproducing an unpublished autobiographical essay Yonge wrote in 1877, intercalated with remarks by Coleridge. The sections of the Life written by Coleridge, conversely, consist of long extracts from Yonge’s letters that take up almost as much space as Coleridge’s own words. Coleridge undertook the biography out of personal friendship for Yonge, and its dialogic form mimics the structure of a social relationship conducted through conversation and correspondence.

The biographer was less an author than an editor who gathered and commented on a subject’s writings without generating an autonomous narrative of her life. Reticence was paradoxically characteristic of Victorian life writing, which was as defined by the drive to conceal life stories as it was indicative of a compulsion to transmit them. This was true of life writing by and about men as well as by and about women. The authors of biographies often did not name themselves directly. Instead they subsumed their identities into those of their subjects. Authors who knew their subjects intimately as children, spouses, or parents usually adopted a deliberately impersonal tone, avoiding the first person whenever possible.

In her anonymous biography of her daughter Mary Duncan, for example, Mary Lundie completely avoided writing in the first person and was sparing even with third-person references to herself as Duncan’s “surviving parent” or “her mother” (243, 297). The materials used in biographies and autobiographies were similarly discreet, and the diaries that formed the basis of much life writing revealed little about their authors’ lives. Victorian life writers who published diary excerpts valued them for their very failure to unveil mysteries, often praising the diarist’s “reserve” and hastening to explain that the diaries cited did “not pretend to reveal personal secrets.”

Although we now expect diaries to be private outpourings of a self confronting forbidden desires and confiding scandalous secrets, only a handful of authenticated Victorian diaries recorded sexual lives in any detail, and none can be called typical. Unrevealing diaries, on the other hand, were plentiful in an era when keeping a journal was common enough for printers to sell preprinted and preformatted diaries and locked diaries were unusual. Preformatted diaries adopted features of almanacs and account books, and journals synchronized personal life with the external rhythms of the clock, the calendar, and the household, not the unpredictable pulses of the heart.

Diaries were rarely meant for the diarist’s eyes alone, which explains why biographers had no compunction about publishing large portions of their subjects’ journals with no prefatory justifications. Girls and women read their diaries aloud to sisters or friends, and locked diaries were so uncommon that Ethel Smyth, born in 1858, still remembered sixty years later how her elders had disapproved when she started keeping a secret diary as a child. Some diarists even explicitly wrote for others, sharing their journals with readers in the present and addressing them to private and public audiences in the future. By the 1840s, published diaries had created a popular consciousness, and self-consciousness, about the diary form.

In 1856, at age fourteen, Louisa Knightley (1842–1913), later a conservative feminist philanthropist, began to keep journals “written with a view to publication” and modeled on works such as Fanny Burney’s diaries, published in 1842. When the working-class Edwin Waugh began to keep a diary in 1847, his first step was to paste into it newspaper clippings about how to keep a journal. One young girl included diary extracts in letters to her cousin in the 1840s. Princess Victoria was instructed in how to keep a daily journal by her beloved governess, Lehzen, and until Victoria became Queen, her mother inspected her diaries daily.

Diarists often wrote for prospective readers and selves, addressing journal entries to their children, writing annual summaries that assessed the previous year’s entries, or rereading and annotating a life’s worth of diaries in old age. Journals were a tool for monitoring spiritual progress on a daily basis and over the course of a lifetime. Diarists periodically reread their journals so that by comparing past acts with present outcomes they could improve themselves in the future. A Beloved Mother: Life of Hannah S. Allen. By Her Daughter (1884) excerpted a journal Allen (1813–1880) started in 1836 and then reread in 1876, when she dedicated it to her daughters: “To my dear girls, that they may see the way in which the Lord has led me.”

Far from being a repository of the most secret self, the diary was seen as a didactic legacy, one of the links in a family history’s chain. Victorian women’s diaries combined impersonality with lack of incident. Although Marian Bradley (1831–1910) wrote, “My diary is entirely a record of my inner life—the outer life is not varied. Quiet and pleasant but nothing worth recording occurs,” she in fact devoted hundreds of pages to recording an outer life that she accurately characterized as regular and predictable. Indeed, the stability and relentless routine that diaries labored to convey goes far to explain why Victorians were so eager to read the poetry that lyrically expressed spontaneous emotion and the novels that injected eventfulness and suspense into everyday life.

Diaries and novels had common origins in spiritual autobiography, and diaries played a dramatic role in Victorian fiction, but although diaries shared quotidian subjects and diurnal rhythms with novels, they were rarely novelistic. Most diarists produced chronicles that testified to a woman’s success in developing the discipline necessary to ensure that each day was much like the rest, and even travel diaries were filled not with impressions but descriptions similar to those found in guidebooks. When something unusually tumultuous took place, it often interrupted a woman’s daily writing and went unrecorded.”

- Sharon Marcus, “Friendship and the Play of the System.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

God I’ve spent too much time on this to waste it so here, what I’ve gathered. Most people already have this information gathered elsewhere, but here’s what I’ve tried to figure out.

A few days/week before August 23rd, 1904- William (Maxwell) Carter’s train crashes. Wolfgang manages to pull it off of him, before William disappears into the desert.

Tuesday April 17, 1906- Maxwell and Charlie disappear after a performance gone wrong. Charlie is officially reported missing, but William Carter was already considered dead after the train crash in the desert.

1910ish-1921. Maxwell starts kidnapping people for the Constant.

EDIT AROUND 1906 or 1907- Wigfrid disappears after a few others, prompting a newspaper to say it was part of a string of disappearances. Presumably 1910-1918, though likely after 1910 if there was already a string of disappearances. Though in the Klei animated short about her, we can see that she disappeared a few days/weeks/months after the San Francisco earthquake, and can be seen reading “The Kronicle.” She might have lived in San Francisco in 1906.

Unknown Time Point- Wes ends up being kidnapped instead of George T. Witherstone.

Before 1919- Wagstaff gives a spider from the Constant to Webber’s father, the same spider that Webber later befriends and is fused with.

March 29, 1911- A library in New York was burned down. Possibly at the same point in time that Wickerbottom disappeared.

April 16th, 1914- Wendy Carter starts hearing strange music. Possibly the day/week/month of her disappearance. She is around 11 at this time, if she was born in 1903. A letter from Jack Carter that is sent from California to William suggests that this was her place of residence at the time of the diary entry was written.

1919- The Voxola PR-76 radio is manufactured. The factory burns down a few days later, with Winona and Wagstaff disappearing into the portal. We see Winona’s theory board in the short depicting this scene, which gives us a lot of information regarding the other survivors and Maxwell/Charlie. Charlie has been missing thirteen years by this scene. Assuming Winona is in her late 20s to early 30s and the fact that Charlie is the youngest sister, this would put Charlie at around late teens to early 20s at the time of her disappearance.

1921- Wilson disappears. We don’t know how time truly works in the Constant, so we can guess that while the others were kidnapped before him, he might have shown up earlier.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tags

[Sometimes updated]

NAOTMAA

(Nicholas, Alexandra, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia and Alexei)

Nicholas II of Russia (1868 - 1918)

Alexandra Feodorovna (1872 - 1918) | Princess Alix of Hesse

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1895 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna (1897 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (1899 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna (1901 - 1918)

Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich (1904 - 1918)

OTMAA

OTMA

Russian Relatives

Alexander II (1818 - 1881)

Maria Alexandrovna (1824 - 1880)

Tsesarevich Nikolai (1843 - 1865)

Alexander III (1845 - 1894)

Princess Eugenia Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg (1845 - 1925)

Maria Feodorovna (1847 - 1928)

Catherine Dolgorukova (1847 - 1922)

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna (1853 - 1920)

Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna the Elder (1854 - 1920)

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (1857 - 1905)

Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (1858 - 1915)

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (1866 - 1933)

Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871 - 1899)

George Alexandrovich Yuryevsky (1872 - 1913)

Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya (1873 - 1925)

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875 - 1960)

Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1878 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna (1882 - 1960)

Princess Irina Alexandrovna (1895 - 1970)

Tikhon Nikolaevich (1917 - 1993)

Guri Nikolaevich (1919 - 1984)

Hesse Relatives

Grand Duke Louis IV (1837 - 1892)

Princess Alice (1843 - 1878)

Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine (1863 - 1950) | Princess Victoria of Battenberg

Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna (1864 - 1918)

Princess Irene of Hesse and by Rhine (1866 - 1953)

Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse (1868 - 1937)

Eleonore of Hesse (1871 - 1937)

Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine (1895 - 1903)

British Relatives

Queen Victoria (1819 - 1901)

Victoria, Princess Royal (1840 - 1901)

Edward VII (1841 - 1910)

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1844 - 1900)

Alexandra of Denmark (1844 - 1925)

Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1848 - 1939)

George V (1865 - 1936)

Louise, Princess Royal (1867 - 1931)

Princess Victoria of Wales (1868 - 1935)

Princess Maud of Wales (1869 - 1938)

Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein (1870 - 1948)

Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna (1876 - 1936)

Other Royals

Elisabeth of Austria (1837 - 1898)

Diary Entries

Queen Victoria

Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich

Nicholas II

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna

Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna

Years

1840s

1849

1850s

1856

1860s

1862

1863

1864

1865

1870s

1872

1873

1874

1875

1877

1878

1880s

1880

1881

1882

1884

1885

1886

1887

1888

1889

1890s

1891

1893

1894

1895

1896

1897

1898

1899

1900s

1900

1901

1902

1903

1904

1905

1906

1907

1908

1909

1910s

1910

1911

1912

1913

1914

1915

1916

1917

1918

Pairs

The Big Pair

The Little Pair

Other People (friends, officers, staff, ect)

Anna Vyrubova (1884 - 1964)

Margarita Sergeevna Khitrovo (1895 - 1952)

Nikolai Pavlovich Sablin (1880 - 1937)

Butakov Alexander Ivanovich (1881 - 1914)

Pavel Voronov (1886 - 1964)

Catherine Schneider (1856 - 1918)

Princess Sonia Orbeliani (1875 - 1915)

Mathilde Kschessinska (1872 - 1971)

My Stuff

My Edits

My Restorations

My Colourisations

Palaces

Peterhof Palace

Moika Palace

Vladimir Palace

Pavlovsk Palace

Alexander Palace

Series

Family Resemblance Series

Portrayal vs The Real Romanovs

Sunny Being Sunny

Other Tags

Asks

Quotes

Reblogs

Edits

Clothing

Undated

Gifs

Letter Extracts

Full Letters

Colourisations

Art

Close-Ups

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library

Theodore Roosevelt

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum

Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation & Institute History Over the past decade the Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University in western North Dakota has pursued the bold mission of digitizing and archiving all of TR’s letters, diaries, photographs, political cartoons, audio and video recordings, and other media. The digital library at www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org now contains more than 50,000 Roosevelt items, freely available and fully searchable on any Internet-capable device. It is the largest collection of primary source materials - and growing.

Puck cartoon, March 27, 1912. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Postcard of Ansley Wilcox House where Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated. Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site.

"My hat is in the ring" pin, 1912. Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site.

Razor commemorating TR's accession to the presidency in 1901. Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site.

TR's diary entry on the death of his wife Alice. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Manuscripts Division.

Sheet music from the Gregory A. Wynn Theodore Roosevelt Collection.

Stereograph of Roosevelt speaking in Keokuk, Iowa, 1903. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and PhotographsDivision. From Digital to Physical The success of the Theodore Roosevelt Center’s work inspired the North Dakota State Legislature during its 2013 session to appropriate $12 million for the construction of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library. An Interpretive Master Plan was prepared by Hilferty & Associates of Ohio, and a new independent nonprofit organization, the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation (TRPLF), was formed to bring the project to fruition.

The TRPLF is now in the process of designing the Library and the exhibits through which it will provide rare insight into Roosevelt’s life, character, and legacy. The Presidential Library will be more than a building or a collection of buildings. The campus will include a convening center and research facility, a museum, and landscaping that invites the visitor into the out-of-doors. It will also feature an authentic re-creation of the Elkhorn Ranch cabin. The TRPLF has retained M. A. Mortenson Company to oversee all elements of design and construction. The Foundation is undertaking a national capital campaign. Source: https://www.trpresidentiallibrary.org/ Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Letter excerpt from Princess Marie of Romania to

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna

Sinaia, 4 August 1903

My dear Mama,

(...)

Ella is very happy here and my children are mad with joy at having her.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

photo: Elisabeth of Hesse (right) smiling at her Romanian cousins, Carol and Elisabeta.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

1903

Postcard from Tsarina Alexandra to Toni Becker-Bracht, her childhood friend

Postmark: Wolfsgarten, 7.11.03 Travel today. E. & the little one* come with us for 10 days. Kisses. A. Thank you (for your) letter, photos.

*Ernst Ludwig and his daughter Elisabeth

source: Briefe der Zarin Alexandra von Russland: an ihre Jugendfreundin Toni Becker-Bracht

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Schloss Rosenau, 16 July 1903

Dearest Missy!

(...)

Ducky has really made up her mind to come to you by the Orient express, after many discussions and obstinacy in wanting to take the other route. Her daughter is coming also, so at present it is all satisfactorily that way. I am pleased for her for this change, as she will feel lonely after Kyrill's departure.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

photo: Capriolen by Barbara Hauck

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

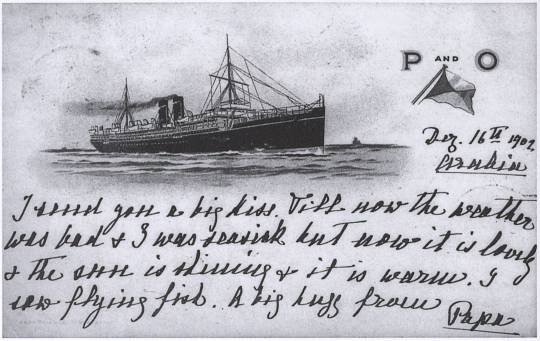

1902-1903 Postcards

In December 1902, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig began his trip to India and Egypt. During his journey, he sent his daughter, Princess Elisabeth of Hesse, numerous postcards, which are preserved in the Hessian State Archives in Darmstadt.

When he departed in December 1902, Ernst Ludwig left his first “Gruss Haus Darmstadt” postcard for his beloved daughter, where he wrote in English: “Goodbye my darling. God bless you. Papa’s love is always near you, sleeping or walking."

On the outward journey, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig sent numerous postcards to Elisabeth, e.g. “tender kisses” from Paris or a picture of his hotel in Marseille with details of his balcony.

On the postcard above, written on board the Arabia on December 16, 1902, Ernst Ludwig told his daughter: "I send you a big kiss. Till now the weather was bad & I was seasick but now it is lovely & the sun is shinning & it is warm. I saw flying fish. A big kiss from Papa.” He celebrated Christmas on board the "Arabia" and Elisabeth sent him and his entourage a Christmas card.

On January 1, 1903, Ernst Ludwig enthusiastically reported to his daughter about his impressions from Delhi: “All those many people dressed in every color of the rainbow. It was lovely. A big kiss from Papa.” The cards are mostly in black and white, but for her daughter to get a better impression, he also described the colours of everything he saw.

On the postcard above, written on January 15, 1903, he wrote: "This lovely place is all in white marble with a blue (sky ?) & lots of green parrots flying about & screaming. They are green with red beak & a red ring round their necks. Papa"

Almost every day he sent his daughter postcards with picturesque pictures and short, sweet greetings. Postcards with motifs that were exotic to Elisabeth document his journey to destinations in northern India that are still classic today, such as Benares, Agra with the Taj Mahal, Jaipur and Fatehpur Sikri.

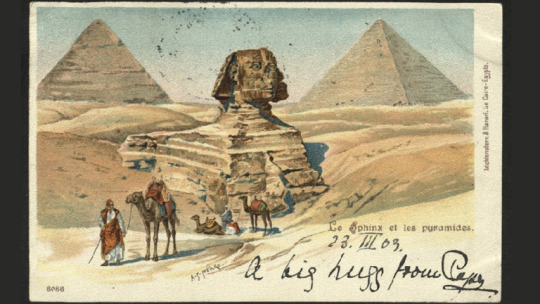

At the end of February, Ernst Ludwig finally began his return journey - but made a stopover in Egypt. On March 5, 1903, on a postcard from the Shephard's Hotel, the most famous luxury hotel in Cairo at that time, Ernst Ludwig announced to his daughter what should not be missed on a trip to Egypt: “Today, I go for a week up the Nile.”

On March 11, 1903, he sent birthday greetings to Elisabeth on a card from Aswan. He also visited Luxor and Karnak and, of course, the pyramids of Giza at the end.

On the postcard above, written on March 22, 1903, he proudly reported to Elisabeth about his climb to the pyramids: "I klimbed (sic.) up the pyramid yesterday & got very out of breath. Today I krept (sic.) into the inside. It was very difficult because all was so very slippery. Papa."

On the postcard above, written on March 23, 1903, Ernst Ludwig sent his daughter "a big hug from Papa".

He finally returned to Darmstadt via Genoa on April 3, 1903. In the following months, Ernst Ludwig continued to send postcards with loving greetings to Elisabeth from his travels through Germany. In one of his last cards, written on August 6, 1903, he told her: “Next time you must come with me.”

source: landesarchivhessen.de Thank you Thomas Aufleger for sharing this little treasure with me!

#princess Elisabeth of Hesse#Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse#1902 Letters & Diary entries#1902#1903 Letters & Diary entries#1903#1902 Biography#1903 Biography

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902-1903 Postcards (part II)

In the past few weeks, the Hessischess Staatsarchiv Darmstadt has made public more postcard sent by Ernst Ludwig to his beloved Elisabeth.

On the postcard below, he wrote to his daughter from Grebenhain. "21 September 1902. Such a nice reception here. A big hugg (sic.) Papa."

In December 1902, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig began his trip to India and Egypt. During his journey, he sent his daughter, Princess Elisabeth, numerous postcards, which are preserved in the Hessian State Archives in Darmstadt.

In his trip, the Grand Duke travelled through Marseille, Port Said, Suez, Aden, Bombay, Delhi, Ducknow, Benares, Agra, Calcutta, Jaipur, Cairo, Aswan, Luxor, Karnak, Philae, Ismailia and Genoa.

His first stop was Marseille, from where he sent his daughter the following postcard: "Dec. 11th. The midle (sic.) balcony is my room. It is warm & sunny here but windy. I only hope it will be goo for tomorrow. (??) go on board. A kiss. Papa."

The Grand Duke started the year 1903 in Delhi (India), from where he sent his daughter the postcard below, with New Year Wishes: "Jan. 1st 1903. All my loving wishes to you darling. Papa."

On the postcard below, he wrote to his daughter from Cairo: "A kiss from Papa".

In Cairo, on his return journey, Ernst Ludwig lodged in the most luxurious hotel in Egypt at the time, the Shepheard's Hotel. From there, he sent his daughter the following postcard:

"5th March 1903. I send you all my love. It is windy & not very warm here. Are you having a happy time? Today I go for a walk up the Nile. A big kiss from Papa."

On the postcard below, Ernst Ludwig wrote to Elisabeth from Lauterbach (Hesse), the last stop in is journey:

"Aug. 5th 1903. This is the Place from where the funny song comes from. All the pictures are put so together that if you look at them sideways they make a stocking. Papa".

source: Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt. Thank you Thomas for sharing these with me!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

1903

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Schloss Rosenau, 5 July 1903

Now, about Ducky coming to you. Kyrill is to leave on the 20th and she proposes going also then to you, I am very pleased that she has come to this resolution. I wish only that the following proposal should come from you first: that she should absolutely bring her daughter, which would only be right and natural. She has not seen that poor child since before Easter, that means for two months and alas! I must add, does not seem to miss her a bit. She is always putting off her coming back... This is natural just at this moment, when she is sticking the whole day long with Kyrill, like an engaged couple and the sharp child would be terribly in the way. But when the principle obstacle removes himself and she goes to you, she ought to take her daughter back at last...

This question is a terribly sad one and I have somehow the feeling that at bottom Ducky would be relieved to get quite rid of this child. If she marries Kyrill it will probably end by it, but at present she must stick to her daughter. Oh! how sad it all is, for selfishness plays the principal part in this love affair and drowns all maternal feeling in her...

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache. The words "absolutely", "ought" and "must" appear underlined in the original letter. 💔

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

1903

Excerpts from Tsar Nicholas II diary entries:

Tsarskoe Selo, February 23rd

Uncle Vladimir and Aunt Miechen drank tea with us. They talked about Kirill and his unfortunate love for Ducky.

Tsarskoe Selo, May 26th

Kirill drank tea with us. Had a conversation with him regarding Ducky.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

1903

Excerpt from Tsar Nicholas II diary entry:

Darmstadt, September 15, 1903

Went to the park in Kranichstein to the Dianaburg pavilion where we had tea with the children.

The following photographs were taken on that day at Dianaburg:

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

1903

Letter excerpt from Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig to his sister, Victoria Mountbatten

Darmstadt, May 29th 1903

“Just that about my child has been worrying me very much and especially because I can't do anything in the matter and you are the only one who can say anything to her [Victoria Melita]. I fear it will be of no use but anyhow I thank you once more with all my heart. It is such a joy to see the child is getting on again and she likes her lessons."

Princess Elisabeth of Hesse posing with her father, her aunt Victoria Mountbatten & her husband and sons on Christmas, 1902.

sources:

letter: Thomas Aufleger from the Hessian State Archives (Danke Thomas!)

image: Mountbatten, eighty years in pictures

31 notes

·

View notes